The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus

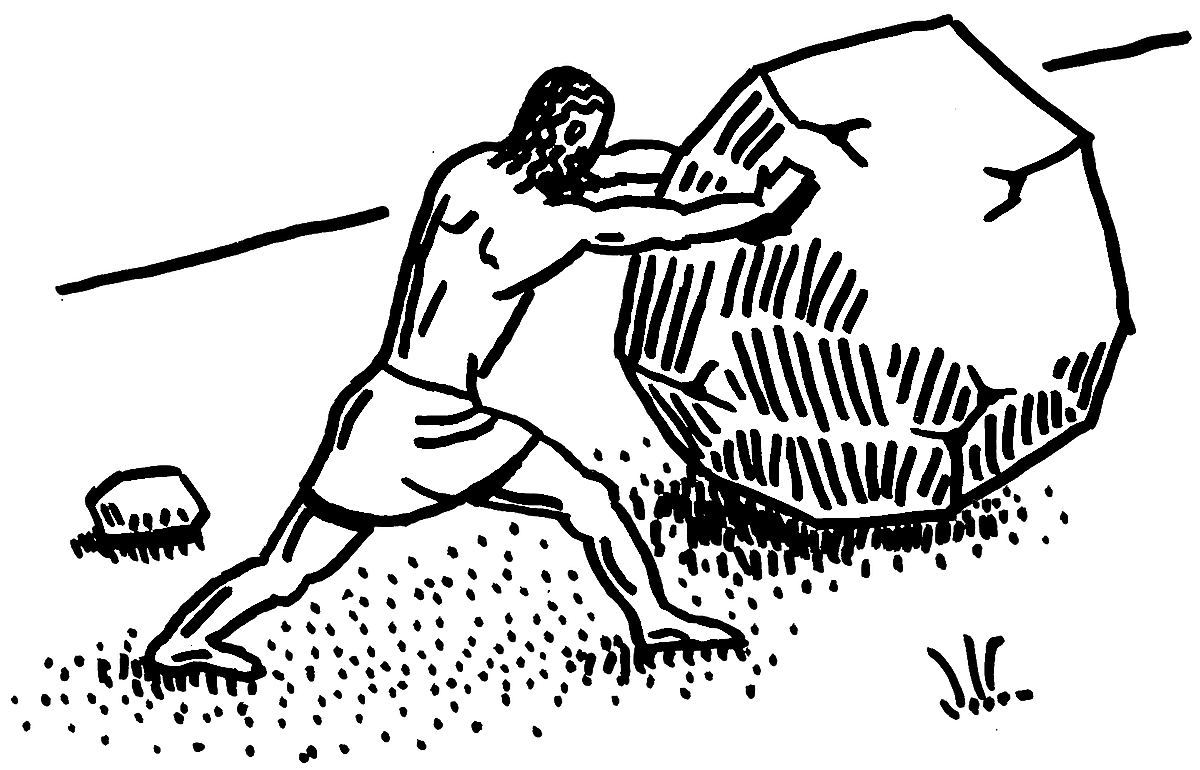

The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.

According to Greek mythology, Sisyphus gets into this situation for his disrespect of gods (stole their secrets), hatred of death (put Death into chains), and love for life (overstayed his temporary resurrection). Maybe so, but those same qualities make him an absurd hero for Camus. He’s living the life he has, not bound by illusions of something more. The lucid hopelessness constitutes Sisyphus’ torture, yet he takes on his fate and thereby turns it into victory. The rock is now his thing.

Is Sisyphus’ condition much worse than ours? After all, what do our efforts and accomplishments ultimately amount to? Sisyphus’ fate is made tragic only by him being conscious of it. But are our lives any less absurd?

Camus thinks the fundamental question of philosophy is whether life is worth living—not least for the actions it entails. If none of the striving and suffering carries eternal meaning, should we just commit suicide to get it over with? No, says Camus, quite the opposite. Life will be lived all the better if there’s no meaning. Living for a transcendent idea or in the hope for an afterlife is not living for life itself.

Our minds relentlessly long for unity, clarity, and certainty. Yet it’s impossible to reduce the world to a rational principle. Camus defines absurd as this fundamental contradiction of what we want and what the world offers to us. Once we become conscious of the absurd, we can’t help but preserve it as the truth, no matter how undesirable it would be. It can’t be replaced with a hope that means nothing anymore.

A stranger to myself and to the world, armed solely with a thought that negates itself as soon as it asserts, what is this condition in which I can have peace only by refusing to know and to live, in which the appetite for conquest bumps into walls that defy its assaults?

Negating either side of the absurd, by trusting universal explanations or rejecting reason altogether, would be escaping the problem. On one hand, science can provide hypotheses that explain but are not certain. On the other hand, we’re certain of our existence but that explains nothing. That being the case, reason still has relative powers as long as we recognize its limits.

To a man devoid of blinders, there is no finer sight than that of the intelligence at grips with a reality that transcends it.

To Camus, fully living life is to profoundly accept it, including the absurd. He believes life gets its value from revolt: defiantly confronting our obscurity, refusing to reconcile. It is not renunciation. Instead of suicide, we should carry on and exhaust everything until the very end.

That revolt is the certainty of a crushing fate, without the resignation that ought to accompany it.

Camus argues there’s no other freedom than the one granted by acknowledging absurdity. After all, our aims and justifications are fundamentally determined by ungrounded convictions of meaning. Life’s apparent purpose urges us to adapt to its demands, making us slaves of our supposed liberty. Understanding this releases us from the beliefs impoverishing our experience and action: absurd freedom emerges. It is not infinite or absolute—but what would that even mean? We can only experience our own freedom—outside ourselves the notion is irrelevant. Camus puts it another way: If God is all-powerful, we’re not free and God is responsible for evil. If we’re free and responsible, God is not all-powerful.

The absurd man thus catches sight of a burning and frigid, transparent and limited universe in which nothing is possible but everything is given, and beyond which all is collapse and nothingness. He can then decide to accept such a universe and draw from it his strength, his refusal to hope, and the unyielding evidence of a life without consolation.

Living according to these ideas doesn’t mean we shouldn’t behave with integrity. Perhaps there’s nothing to build a moral code on but we still have to bear the consequences of our actions. We’re not guilty but we’re responsible. I take this to mean the foundations of ethics are subjective and implicit but important and shared by most to a degree.

Camus’ illustrations of characters embracing the absurd are expending themselves, not living in hope or for the future. Instead of explaining and solving, they are experiencing and describing. Their art is not an escape from the absurd but an expression of it. Their conquest is not advancing a supreme cause but overcoming themselves. Their love is not a participation in something eternal but desire, affection, and intelligence binding to someone.

The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus. Original title: “Le mythe de Sisyphe”. First published in 1942. I read the 1955 English translation by Justin O’Brien.